Istorya Studios, Inc.

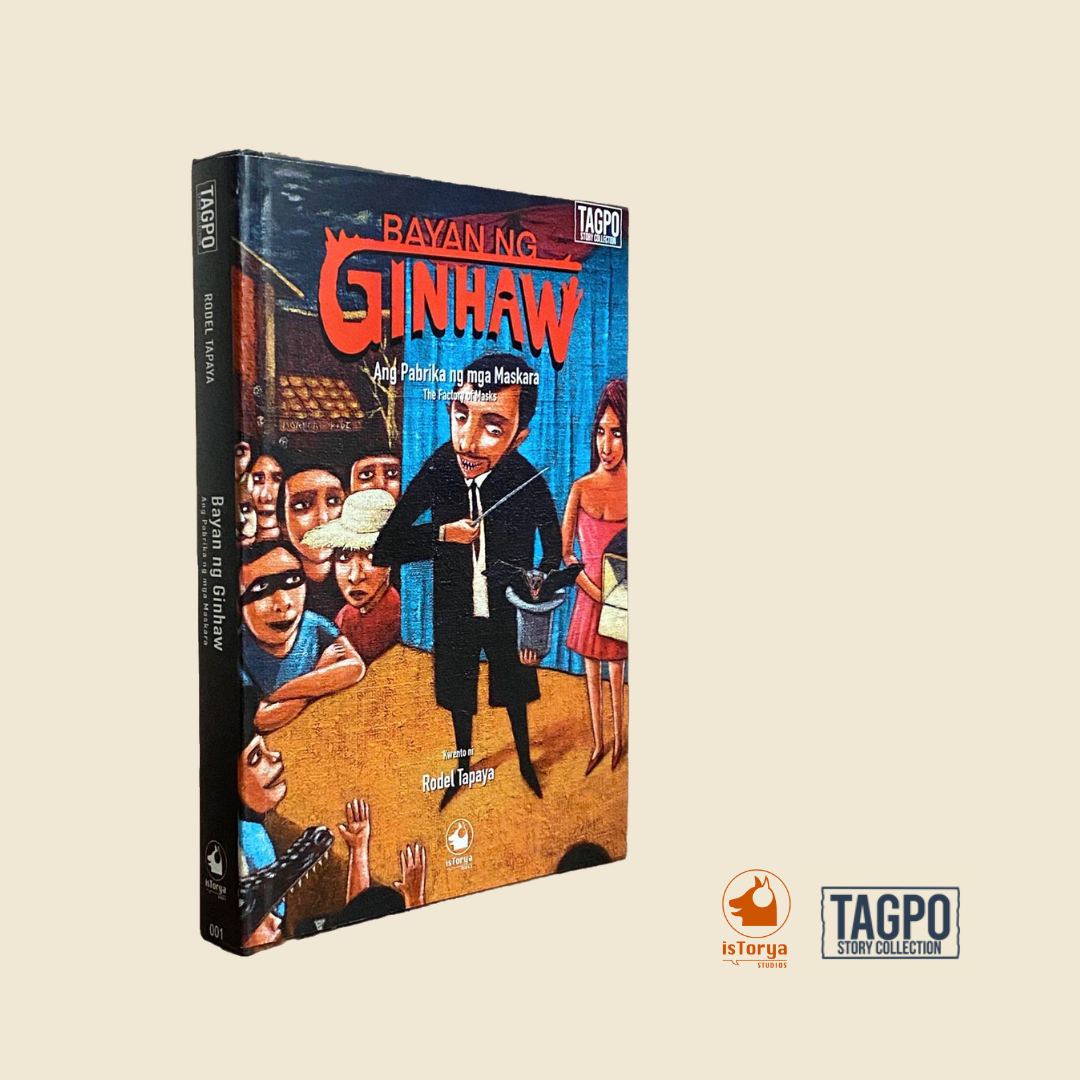

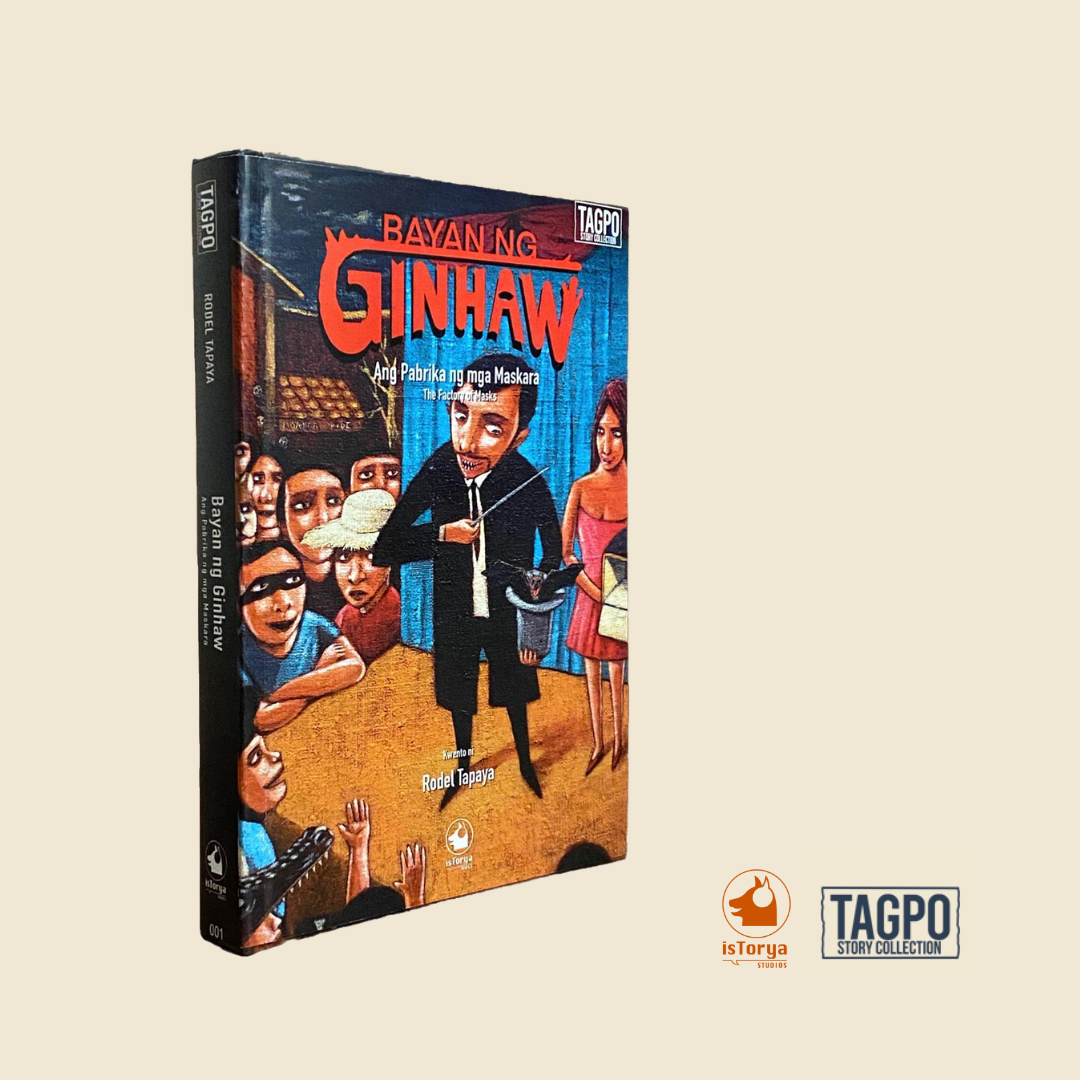

Bayan ng Ginhaw by Rodel Tapaya (Hardcover)

Regular price

₱1,200.00

Sale price

₱1,200.00

Regular price

Unit price

per

Tax included.

Novel in Pictures by Rodel Tapaya

Bayan ng Ginhaw: Origins of a Fictional Atlas

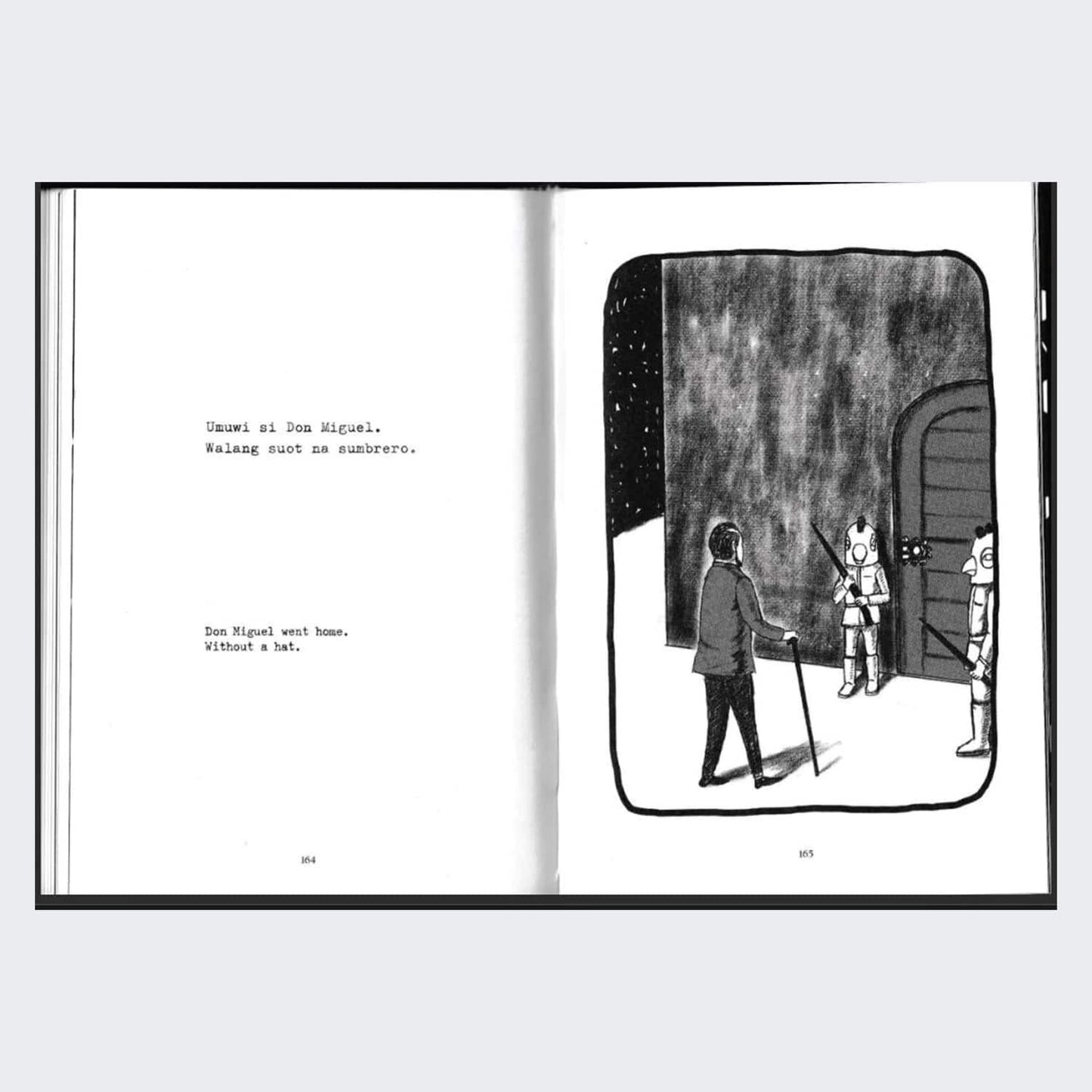

The fictional Bayan ng Ginhaw first appeared in Rodel Tapaya’s eponymous painting in the 2005 exhibition Lunan (Place) held in Boston Gallery. In the work, Ginhaw is seen from a deconstructed map of roads and buildings over a distorted grid. The coordinates flicker like stars in the night that wrap around vignettes of the town’s institutions: the church, the school, the factory, and the tower inhabited by characters such as Pitang Tsismosa, Emong Manlalakbay, Mang Bel, and Don Miguel. These characters serve as allegories for typical personalities found in a Filipino town.

Inspired by Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Macondo, a fictional town in the novel One Hundred Years of Solitude, Ginhaw initially drew from the neighborhood and personalities of Tapaya’s childhood in Montalban, Rizal Province. Located at the foothills of Luzon’s Sierra Madre Mountain Range, Montalban is the setting of many Filipino legends that have appeared in a refracted form in Tapaya’s series of works over many years.

The name Ginhaw is derived from Maginhawa, a street in Quezon City, now a bustling restaurant belt, which used to be a quiet hub for students and teachers who live off the University of the Philippines campus. This was the site of Tapaya’s first studio, which he shared with wife Marina Cruz-Garcia in 2004.

The etymology of Tapaya’s fictional town is worth examining. The word Ginhawa is from the Proto-Philippine “nihawa” (breath) which was used by Philippine revolutionaries to convey the aspirations of the Katipunan movement. Early dictionaries take Ginhaw to refer to bodily comfort often caused by good health. In colloquial use, the word often means “to improve”. Unlike kasaganaan, which refers to material wealth, kaginhawaan was specifically defined in the 1613 San Buenaventura Dictionary as the feeling of being delivered from sickness or suffering. It is in this understanding that ginhawa takes on a socio-political meaning that is beyond bodily comfort.

In the poem Pag-ibig sa Tinubuang Lupa (Love for the Motherland), the Katipunan leader Andres Bonifacio, bid the masses to seek ginhawa for the bayan because the nation’s well-being meant ginhawa for all people. Tapaya’s Bayan ng Ginhaw exhorts us to do the same via an aggregate of personal experience and an appreciation of Philippine history. As a setting for his graphic novel about physical and moral crippling, Bayan ng Ginhaw bears the painter’s clearest statement and sentiment about the fate of the country.

Couldn't load pickup availability